What is Peptic Ulcer Disease (PUD)?

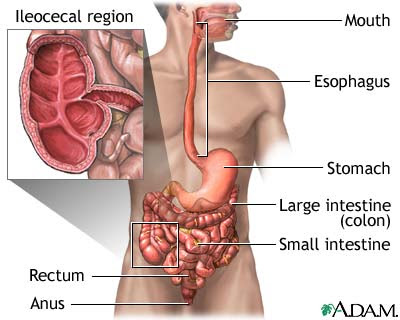

A peptic ulcer is a hole in the gut lining of the stomach, duodenum, or esophagus. A peptic ulcer of the stomach is called a gastric ulcer; of the duodenum, a duodenal ulcer; and of the esophagus, an esophageal ulcer.

The two most common causes of peptic ulcer disease are Helicobacter pylori infection and the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). As the prevalence of H. pylori infection decreases and NSAID use increases, the relative contribution of each factor to the incidence of peptic ulcer disease (PUD) will change.

What is H. pylori?

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) is a type of bacteria. Researchers believe that H. pylori is responsible for the majority of peptic ulcers.

H. pylori infection is common in the United States. About 20 percent of people under 40 years old and half of those over 60 years have it. Most infected people, however, do not develop ulcers. Why H. pylori does not cause ulcers in every infected person is not known. Most likely, infection depends on characteristics of the infected person, the type of H. pylori, and other factors yet to be discovered.

Researchers are not certain how people contract H. pylori, but they think it may be through food or water.

Researchers have found H. pylori in the saliva of some infected people, so the bacteria may also spread through mouth-to-mouth contact such as kissing.

How does H. pylori cause a peptic ulcer?

H. pylori weakens the protective mucous coating of the stomach and duodenum, which allows acid to get through to the sensitive lining beneath. Both the acid and the bacteria irritate the lining and cause a sore, or ulcer.

H. pylori is able to survive in stomach acid because it secretes enzymes that neutralize the acid. This mechanism allows H. pylori to make its way to the "safe" area—the protective mucous lining. Once there, the bacterium's spiral shape helps it burrow through the lining.

Peptic Ulcer Causes

Normally, the lining of the stomach and small intestines are protected against the irritating acids produced in your stomach. If this protective lining stops working correctly, and the lining breaks down, it results in inflammation (gastritis) or an ulcer.

No single cause has been found for ulcers. However, it is now clear that an ulcer is the end result of an imbalance between digestive fluids in the stomach and duodenum. Ulcers can be caused by:

- Infection with a type of bacteria called Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori)

- Use of painkillers called nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as aspirin, naproxen (Aleve, Anaprox, Naprosyn, and others), ibuprofen (Motrin, Advil, Midol, and others), and many others available by prescription. Even aspirin coated with a special substance can still cause ulcers.

- Excess acid production from gastrinomas, tumors of the acid producing cells of the stomach that increases acid output; seen in Zollinger-Ellison syndrome.

- Drinking too much alcohol

- Smoking cigarettes or chewing tobacco

- Being very ill, such as being on a breathing machine

- Radiation treatments

- Stress. Although stress per se isn't a cause of peptic ulcers, it's a contributing factor.

A rare condition called Zollinger-Ellison syndrome causes stomach and duodenal ulcers. Persons with this disease have a tumor in the pancreas that releases high levels of a hormone, which causes an increase in stomach acid.

Depending on their location, peptic ulcers have different names:

- Gastric ulcer. This is a peptic ulcer that occurs in your stomach.

- Duodenal ulcer. This type of peptic ulcer develops in the first part of the small intestine (duodenum).

- Esophageal ulcer. An esophageal ulcer is usually located in the lower section of your esophagus. It's often associated with chronic gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).

Peptic Ulcer Symptoms

Small ulcers may not cause any symptoms. Some ulcers can cause serious bleeding.

Abdominal pain is a common symptom but it doesn't always occur. The pain can differ a lot from person to person.

* Feeling of fullness -- unable to drink as much fluid

* Hunger and an empty feeling in the stomach, often 1 - 3 hours after a meal

* Mild nausea (vomiting may relieve symptom)

* Pain or discomfort in the upper abdomen

* Upper abdominal pain that wakes you up at night

Other possible symptoms include:

* Bloody or dark tarry stools

* Chest pain

* Fatigue

* Vomiting, possibly bloody

* Weight loss

* Heartburn

Peptic Ulcer Exams and Tests / Peptic Ulcer Diagnosis

To diagnose an ulcer, your doctor will order one of the following tests:

- Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) is a special test performed by a gastroenterologist in which a thin tube with a camera on the end is inserted through your mouth into the GI tract to see your stomach and small intestine. During an EGD, the doctor may take a biopsy from the wall of your stomach to test for H. pylori.

- Upper gastrointestinal (upper GI) X-ray. Upper GI is a series of x-rays taken after you drink a thick substance called barium.

- Hemoglobin blood test to check for anemia

- Stool antigen test. This test checks for H. pylori in stool samples. It's useful both in helping to diagnose H. pylori infection and in monitoring the success of treatment.

- Breath test. This procedure uses a radioactive carbon atom to detect H. pylori. The advantage of the breath test is that it can monitor the effectiveness of treatment used to eradicate H. pylori, detecting whether the bacteria have been killed or eradicated.

Peptic Ulcer Treatment

Treatment involves a combination of medications to kill the H. pylori bacteria (if present), and reduce acid levels in the stomach. This strategy allows your ulcer to heal and reduces the chance it will come back.

Take all of your medications exactly as prescribed.

If you have a peptic ulcer with an H. pylori infection, the standard treatment uses different combinations of the following medications for 5 - 14 days:

- Two different antibiotics to kill H. pylori, such as clarithromycin (Biaxin), amoxicillin, tetracycline, or metronidazole (Flagyl)

- Proton pump inhibitors such as omeprazole (Prilosec), lansoprazole (Prevacid), or esomeprazole (Nexium)

- Bismuth (the main ingredient in Pepto-Bismol) may be added to help kill the bacteria

If you have an ulcer without an H. pylori infection, or one that is caused by taking aspirin or NSAIDs, your doctor will likely prescribe a proton pump inhibitor for 8 weeks.

You may also be prescribed this type of medicine if you must continue taking aspirin or NSAIDs for other health conditions.

Other medications that may be used for ulcer symptoms or disease are:

- Misoprostol, a drug that may help prevent ulcers in people who take NSAIDs on a regular basis

- Medications that protect the tissue lining (such as sucralfate)

If a peptic ulcer bleeds a lot, an EGD may be needed to stop the bleeding. Surgery may be needed if bleeding cannot be stopped with an EGD, or if the ulcer has caused a perforation.

Peptic Ulcer Outlook (Prognosis)

Peptic ulcers tend to come back if untreated. If you follow your doctor's treatment instructions and take all of your medications as directed, the H. pylori infection will be cured and you'll be much less likely to get another ulcer.

Peptic Ulcer Prevention

Avoid aspirin, ibuprofen, naproxen, and other NSAIDs. Try acetaminophen instead. If you must take such medicines, talk to your doctor first. Your doctor may:

- Test you for H. pylori first

- Have you take proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) or an acid blocker

- Have you take a drug called Misoprostol

The following lifestyle changes may help prevent peptic ulcers:

- Do not smoke or chew tobacco.

- Limit alcohol to no more than two drinks per day.

- Avoid nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

- Control acid reflux. If you have an esophageal ulcer — usually associated with acid reflux — you can take several steps to help manage acid reflux.

Synonyms and Keywords

aspirin, bleeding ulcer, bowel obstruction, digestive diseases, digestive tract, stomach ulcers, dual therapy, duodenal ulcers, duodenum, fecal-oral transmission, gastric ulcers, gastrointestinal tract, GI tract, Helicobacter pylori, H pylori, H pylori infection, intestinal bleeding, intestinal erosion, intestinal obstruction, intestinal perforation, mucous membranes, mucus, gastric juice, stomach acid, abdominal pain, hydrochloric acid, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, NSAIDs, peptic ulcer disease, PUD, small intestine, stomach, triple therapy, pepsin, vagotomy, antrectomy, ulcer, ulcers, peptic ulcer, peptic ulcers

resource: medlineplus